What are Climate Change Vulnerability Assessments?

Climate Change Vulnerability Assessments (CCVAs) are emerging tools that can be used as an initial step in the adaptation planning process.

A CCVA focuses on species, habitats, or systems of interest, and helps identify the greatest risks to them from climate change impacts. A CCVA identifies factors that contribute to vulnerability, which can include both the direct and indirect effects of climate change, as well as the non-climate stressors (e.g., land use change, habitat fragmentation, pollution, and invasive species?).

Vulnerability assessments are done for local communities to evaluate where and how communities or systems will be vulnerable to climate change. There are several organisations and tools used by the international community and scientists to assess climate vulnerability.

For example, the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MoEF&CC) in India published a framework for doing vulnerability assessments of communities in India.

Vulnerability assessment is a key aspect of anchoring assessments of climate change impacts to present development planning. Methods of vulnerability assessment have been developed over the past several decades in natural hazards, food security, poverty analysis, sustainable livelihoods and related fields. These approaches provide a core set of best practices for use in studies of climate change vulnerability and adaptation.

Vulnerability varies widely across peoples, sectors and regions.

Vulnerability is directly related to climate risks, which is the risk assessments based on formal analysis of the consequences, likelihoods and responses to the impacts of climate change and how societal constraints shape adaptation options.

There is no standard method or framework to conduct a CCVA, and a variety of methods are being implemented at government, institutional, and organisational levels. Because of this, interpretation of CCVA results should carefully consider whether and how each of the three components of vulnerability (exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity) were evaluated, if non-climate stressors were included in the assessment, how uncertainty is presented, the geographic location covered by the assessment, and whether the entire life cycle of a target species was evaluated, particularly for those that are migratory.

Generally, the approach chosen should be based on the goals of practitioners, confidence in existing data and information, and the resources available (e.g., financial, personnel).

Some of the most common frameworks applied regionally are:

NatureServe Climate Change Vulnerability Index (CCVI) – A quantitative assessment based on the traits of fish, wildlife, and habitats that might make them more vulnerable to climate change. The CCVI is suitable for assessing large numbers of species and comparing results across taxa.

It is based in Microsoft Excel, relatively easy to use, and includes factors related to direct and indirect exposure, species-specific sensitivity, and documented or modelled responses to climate change.

Climate Change Response Framework (CCRF) – A collaborative, cross-boundary approach among scientists, managers, and landowners designed to assess the vulnerability of forested habitats. The assessment incorporates downscaled climate projections into tree species distribution models to determine future habitat suitability.

Experts conduct a literature review to summarise the effects of climate change, as well as non-climate stressors, and consider all three components of vulnerability to come to a consensus on a vulnerability ranking and level of confidence.

Northeast Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (NEAFWA) Habitat Vulnerability Model – An approach created to consistently evaluate the vulnerability of all non-tidal habitats across thirteen Northeastern US states. This method is based on an expert-panel approach, and is made up of 4 sections, or modules, based in Microsoft Excel. The modules score vulnerability based on climate sensitivity factors (adaptive capacity is also partially addressed) and non-climate stressors to produce vulnerability rankings and confidence scores.

Experts use these scores to construct descriptive paragraphs explaining the results for each species or habitat evaluated. These narratives help to ensure transparency, evaluate consistency, and clarify underlying assumptions. The National Park Service, the U.S. Forest Service, and several states have used this model successfully to assess habitat vulnerability.

Expert opinion workshops and surveys – These are often qualitative (or mixed qualitative/quantitative), and have been used by a number of states including a report on habitat vulnerability in Massachusetts.

These assessments are usually developed independently, and are typically not based on a standardised framework. This allows greater flexibility for the institution conducting the CCVA; however, it is more difficult to make direct comparisons across assessment results since the specific factors evaluated may vary.

In the third technical paper of IPCC the method of climate change vulnerability assessment has been discussed. In this paper the climate change vulnerability assessment strategies are discussed in few steps (tasks):

Vulnerability framework and definitions: This denotes the process of defining the vulnerability in regional perspective and designing the vulnerability assessment framework by reviewing existing regional or national assessments that relate to vulnerability- e.g. national development plans, poverty reduction papers, environmental sustainability plans and natural hazard assessment. The already existing framework can be used as a base for climate change vulnerability assessment. If no framework is available, stakeholder-led exercises are valuable in this respect.

Constructing a development baseline and targeting vulnerable groups: The second task is to review present conditions in order to target vulnerable groups and establish a development baseline. Who are vulnerable? To what? Where? etc.

As above, the starting point should be existing vulnerability assessments. Many developing countries have produced related inventories, such as poverty maps, human development indices, and environmental sustainability indices. The development baseline should incorporate two levels of analysis:

A comprehensive set of spatial indicators of vulnerability (VI)

Identification of target vulnerable groups that are a priority for adaptation policy.

Vulnerability is a relative measure, it does not exist as something we can observe and measure. Therefore, indicators can only be selected based on choices by the technical team, stakeholders and the vulnerable themselves.

The choice of the target of the vulnerability assessment should be related to the problems identified in scoping the project. A fundamental issue is whether the target is people, resources or economic activities, or regions.

Food security focus for social vulnerability

Biodiversity focus for ecosystem services.

The output of this task is a set of vulnerability indicators (labelled VI) and identification of vulnerable livelihoods (or other targets), that together form a baseline of present development. The collation of vulnerability indicators underpins the analyses and identification of priorities for adaptation.

Linking the development baseline to climate impacts and risks: The first two tasks establish present conditions of development; the next step is to refine the analysis and link the development baseline explicitly to climate impacts and risks.

It may be that risk maps of present climatic variations are already available. Certainly, almost all countries will have national models of agricultural production and hydrological sensitivity to climatic variations, for example. If so, these can be added to the indicator data set. If quantitative impact assessments are not available, it should be possible to develop indicators of present climatic risks. Historical episodes, such as the drought of record or extreme rainfall during historical storms can help define at-risk regions. If formal models of (present) climate impacts and data on climatic risks are not available, expert opinion and case examples from similar countries can be used to develop a suite of plausible impacts scenarios.

The output from this task is an understanding of the present probability of a range of climatic conditions and hazards. The conjunction of the climatic hazards and development baseline comprises the present climate vulnerability.

Drivers of vulnerability: linking the present and future: At this point the vulnerability database (VI) includes climatic risks and identification of target vulnerable groups (Vg).

It is a useful snapshot of present vulnerability reflected in a range of indicators. The next step is to provide a more qualitative understanding of the drivers of vulnerability— what shapes exposure to climatic risks? At what scales?

This analysis links the present (snapshot) with pathways of the future--that may lead to sustainable development or further vulnerabilities.

The techniques for ‘mapping’ the structure of present vulnerability and how it might change in the future are likely to be qualitative in the first instance. Interactive exercises (such as cognitive mapping) amongst experts and stakeholders can help refine the initial VA framework (Task I) by suggesting linkages between the vulnerable groups, socio-institutional factors (e.g social networks, regulation and governance), their resources and economic activities, and the kinds of threats (and opportunities) resulting from climatic variations. Thought experiments, case studies, in-depth semi-structured interviews, discourse analysis, and close dialogue are social science approaches that have application in understanding the dynamics of vulnerability. The best strategy is to start with exploratory charts and checklists—which can help identify priorities and gaps—before adopting specific quantitative analyses.

Outputs of this task are qualitative descriptions of the present structure of vulnerability, future vulnerabilities and a revised set of VIs that include future scenarios.

Outputs of the vulnerability assessment: The outputs of a vulnerability assessment include:

A description and analysis of present vulnerability, including representative

vulnerable groups (for instance specific livelihoods at-risk of climatic hazards).

Descriptions of potential vulnerabilities in the future, including an analysis of

pathways that relate the present to the future.

Comparison of vulnerability under different socio-economic conditions, climatic

changes and adaptive responses.

The final task is to relate the range of outputs to stakeholder decision making, public awareness and further assessments. These topics are framed in the overall APF design and stakeholder strategy.

The first consideration is whether stakeholders and decision makers already have decision criteria that they apply to strategic and project analyses. For instance, the Millennium Development Targets may have been adopted in a development plan. If so, can the set of vulnerability indicators (VI) be related to the MDTs? Is there an existing map of development status that can be related to the indicators of climate vulnerability? It is always better to relate the vulnerability assessment to existing frameworks, terminology and targets than to attempt to construct a new language solely for the climate change issues.

Historically, a common approach has been to aggregate the individual indicators into an overall score (here called an index. For example, the Human Development Index is a complex index of five indicators.) using statistical techniques.

Another aggregation technique is to cluster vulnerable groups (or regions) according to key indicators. More formal methods for clustering, such as principal components analysis, are becoming more common as well.

Finally, the qualitative understanding of vulnerability can be developed as stories. Storylines are part of the many socio-economic scenarios. Within the scenario storyline, hypothetical stories about representative livelihoods are effective ways to portray the conditions of vulnerability and the potential futures of concern. The communication methods are diverse--articles from future newspapers, radio documentaries and interviews can all be effective.

The output should link to further steps in the Adaptation Planning Framework.

‘A Framework for Climate Change Vulnerability Assessments’ prepared by MEFCC, GoI put forward a detailed framework for climate change vulnerability assessment with examples.

The two common methods of vulnerability assessment are the top-down approach and bottom-up approach.

Top-down approaches (end-point) start with an analysis of climate change and its impacts. Usually preferred at global, national or regional levels and most common in climate impacts and vulnerability studies. This method concentrates on the biophysical effects of climate change.

Top-down approach explicitly considers the existing adaptive capacities and strategies that can reduce negative impacts of climate change. It has the ability to represent direct cause-effect relationships of climate stimuli and their biophysical impacts.

Bottom-up approaches (starting-point) start with an analysis of people affected by climate change. Usually used at the local level. It provides an analysis of what causes people to be vulnerable to natural hazards. It is developed from disaster risk reduction, humanitarian aid and community development. It takes into account the fact that not all social groups are equally vulnerable and vulnerability may differ in class, occupation, ethnicity, caste, gender, disability, age, health status etc. it is participatory (Participatory Rural Appraisal) in nature. Unlike top-down approach it focuses on assessment of current vulnerability rather than trying to assess future vulnerability. It considers collecting information from local areas and does not rely on model generated climatic data.

Top-down approaches focus mostly on the biophysical impacts of climate change but say less about why, which and how people are vulnerable. Bottom-up approaches, on the other hand, mainly provide information about the vulnerability of different social groups.

Stages and steps

Following table on the following page summarises the general framework for a vulnerability assessment. It is organised in four stages. Each stage consists of multiple steps. The first stage consists of defining the purpose of the vulnerability assessment. These steps are iterative in nature. In every step involvement of all stakeholders must be ensured.

Stage-1: Defining the purpose:

A clear definition of the purpose of the vulnerability assessment is a prerequisite to its planning. Hey, climate change vulnerability assessment is always directed towards a particular user or audience who will be using the result of the assessment e.g. a state or national government.

Vulnerability assessment may be carried out for various purposes.Generally speaking, the purpose of a vulnerability assessment is to inform decision making. Six broad categories of purposes, are as follows:

Identify my mitigation targets.

Identify particularly vulnerable people, regions or sectors.

Raise awareness of climate change.

Allocate adaptation funds to particular vulnerable regions, sectors or groups of people.

Performance of adaptation policy and interventions.

Conduct scientific research.

The specific purpose of the assessment of vulnerability in flood prone West Bengal was to assess the vulnerability of agriculture based livelihoods to shifting rainfall patterns, erratic rainfall and micro level waterlogging conditions.

Stage-2: Planning the vulnerability Assessment:

The planning stage can be one of the most research-intensive stages of a vulnerability assessment study.

Step-1: Se the boundaries of the vulnerability assessment

Defining the resources available for the assessment: (Financial resources, human resources (including skilled personnel) and time)

Define the system of interest: (Vulnerability assessment can be carried out at different regional scales. The area of system of interest can be delimited by either socio-economic boundaries- country, state, district, community/ groups or natural/ecological boundaries- river basin, agro-climatic zone)

Define the unit of measurement: (The measurement unit for collecting data/information is selected as per the purpose and the system of interest. It may be administrative of socio-economic units e.g. district, block, village, household, gender group or natural/ecological units e.g. river sub-basin, watersheds, agro-climatic zones etc.)

Data availability: (Most important deciding factor while selecting methods, tools and levels.)

Step-2: Define the general approach of the vulnerability assessment

Approach of vulnerability assessment depends on purpose, focus, system of interest, unit of measurement and availability of resources. Either of the top-down or bottom-up approach may be selected.

Stage-3: Assessing Current Vulnerability

The objective of a current vulnerability assessment is to identify current vulnerability conditions based on past and current exposure, and the sensitivities and adaptive capacities of the system of interest.

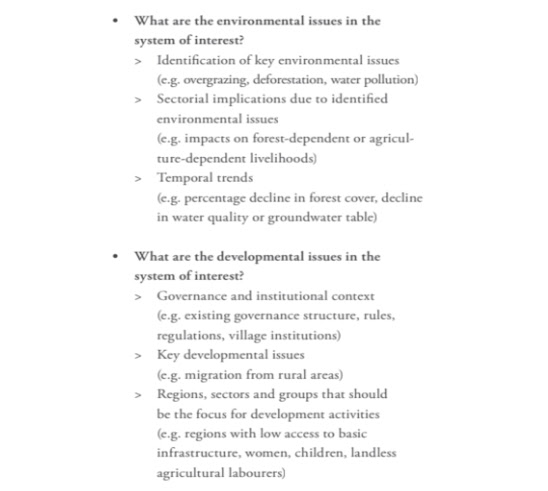

Step-1 Assess the Profile of System of Interest- based on available information on natural resources, state of development and socio-economic and environmental issues.

The current vulnerability assessment provides insights on past-observed climatic trends and factors (exposure) that have contributed to the vulnerability of the system of interest (sensitivity). Current vulnerability assessments also provide an opportunity to learn from adaptive responses in the past (adaptive capacity) – both failures and successes – and thus enable the design of future adaptation responses or adjustments in ongoing climate change adaptation programmes.

There is no predefined set of questions or topics available for studying the profile of the system of interest. However, the following list provides recommendations on formulating key questions to understand the profile of the system of interest.

Suggested models and tools: Bottom-up approach

Step-2: Assess the observed climate (exposure): Past observed climatic trends, variability and extremes in the system of interest provide information on the current exposure of the region in question. Specific questions can define how information should be collected in order to assess the observed climate in relation to exposure.

Suggested methods and tools: Top-down approach (Global and regional climate models, statistical analysis of climate data time series) and bottom-up approach (Hazard trend analysis, oral histories, seasonal calendars)

Step-3: Assess the effects of climate stimuli on the system of interest (Sensitivity)

The sensitivity of a system basically describes the dose-effect relationship between its exposure to climatic stimuli and the resulting impacts. Sensitivity is analysed by determining whether the system of interest is significantly affected by climate-related stimuli or not. If the system is affected by climate-related stimuli, particularly current climate variability and extreme events, it should be considered sensitive.

In this step, information on the impact of climate stimuli on the identified sectors of the system of interest is collected at the level of the unit of measurement.

Suggested methods and tools: 1) Top-down:

Driving forces-Pressures-State-Impacts Responses (DPSIR) framework.

Indicator based methods.

Sector- specific simulation models: (Agriculture, water, coastal mareas, human health, terrestrial ecosystem)

Statistical analysis

2) Bottom-up

Climate hazard trend analyses

Community mapping

Household surveys

Participatory scenario analysis: ‘What if?’ tool

Stakeholder consultations

Timelines

Transect walks

Step 4: Assess the responses to climate variability and extremes (adaptive capacity)

This stage assesses the capacity of the system of interest to respond and adapt to climate change. This is achieved through assessing how the system has adapted or is adapting to current climate variability and extremes and assessing underlying capacities that may allow further adaptation in the future. Adaptive capacity exists at different scales (family, community, region and nation) and is fundamentally dependent on access to resources. Sufficient resource availability is a prerequisite of adaptive capacity. However, the system requiring the resources for adaptation must also be able to mobilise them effectively. Following types of resources are required for assessment of adaptive capacity to climate change.

Step 4 helps in understanding the existing capacities to respond to climatic stimuli and in identifying factors that have enabled effective responses to climatic hazards in the past. A range of questions can be considered in this step.

Step-5: Assess the overall current vulnerability:

The overall current vulnerability of the system of interest is prepared by combining the outputs from Steps 1 to 4 of Stage 3, namely: 1. Assess the profile of the system of interest; 2. Assess the observed climate (exposure); 3. Assess the effects of climate stimuli on the system of interest (sensitivity); 4. Assess the responses to climate variability (adap-

tive capacity). The following key questions should be asked to develop links between the previous steps of the assessment.

Suggested methods and tools: 1) Top-down

• Indicator-based methods

• Sector-specific simulation models

> agriculture

> water

> coastal areas

> human health

> terrestrial ecosystems

2) Bottom-up

• Brainstorming

• Climate hazard trend analyses

• Cognitive mapping

• Community mapping

• Focus group discussions

• Hazard mapping

• Impact matrices

• Participatory scenario analysis: ‘What if?’ tool

• Seasonal calendars

• Transect walks

• Vulnerability matrices

Stage-4; Assess the future vulnerability

This stage comprises four steps for assessing the future vulnerability of the system of interest. It builds on earlier stages during which current climate conditions were analysed and current climate vulnerability was assessed. This is done under the assumption that adapting to current climate variability and extremes will reduce vulnerability to climate change in the future.

Future vulnerability assessments link projections of the future climate and projections of socio-economic development (non-climatic factors) to possible future scenarios. The projections vary both spatially and temporally and show long-term changes in climatic and socio-economic variables.

Step-1: Assess the future climate (future exposure):

This step attempts to determine how climatic variables will change in the future. Top-down vulnerability assessments use climate models to project the effect of higher levels of greenhouse gases (GHG) on the earth’s climate.

Suggested methods and tools:

Global Climate Modelling (GCM) projections

Regional Climate Modelling (RCM) projections

Step-2: Assess the future impacts (future sensitivity):

Step 2 of the assessment of future vulnerability will assess how the current vulnerabilities are likely to be affected by the projected changes in climate variables. For top-down approaches, this step involves the use of specific biophysical models to come up with scenarios of sensitivity to future exposure for individual sectors (e.g. agriculture, forests, water and coastal areas). Such sector models attempt to describe future scenarios by integrating the outputs of climate projections and socio-economic scenarios. Top-down assessments of future sensitivity using simulation models are a data-intensive exercise that requires skilled personnel.

Suggested Methods and tools:

Indicator-based methods

Sector-specific simulation models

Step-3: Assess the future socio-economic scenario (adaptive capacity):

Step 3 of the assessment of future vulnerabilities involves the development of socio-economic scenarios. Assessments may consider human population growth patterns in the system of interest, economic shifts or land use changes.

In future-explicit top-down assessments, socio-economic scenarios are key drivers of projected changes in future GHG emissions and climate variables. They are also key determinants of most climate change impacts, potential adaptations and vulnerability.

Questions:

What are the socio-economic scenarios that can emerge? (Regions, groups, time frame)

What possible measures exist for adapting to climate change in the future?

How will existing capacities for adapting to climate change develop in the future?

Suggested methods and tools:

1) Top-down

Statistical techniques

Ratio method for population growth

Trend Analysis

Modelling techniques

Agent-based modelling

Dynamic Interactive Vulnerability Assessment (DIVA)

Integrated Model to Assess the Greenhouse Effect (IMAGE)

RamCo and ISLAND MODEL

The South Pacific Island Methodology (SPIM)

Step-4: Assess the overall future vulnerability

No comments:

Post a Comment